Some rough lab notes on how to do integer math with computers. Surprisingly deep topic! Usual caveat applies, this is just what I’ve learned so far and there may be inaccuracies. This is mainly from a C/C++ perspective, though there is a small discussion of Rust included.

It all starts with a simple prompt:

return_type computeBufferSize(integer_type headerLen, integer_type numElements, integer_type elementSize)

{

// We conceptually want to do: headerLen + (numElements * elementSize)

}

How do we safely do something as simple as this arithmetic expression in C/C++? Furthermore, what type do we choose for integer_type and return_type?

Overflow

- You can’t just do

headerLen + (numElements * elementSize) literally, because that can overflow for valid input arguments

- Why is overflow bad?

- Reason 1: Logic errors. The result of the expression will wrap around, producing incorrect values. At best they will make the program behave incorrectly, at medium they will crash the program, and at worst, they will be security vulnerabilities.

- Reason 2: Undefined behavior. This only applies to overflow on signed types. Signed overflow is UB, which means the fundamental soundness of the program is compromised, and it can behave unpredictably at runtime. Apparently this allows the compiler to perform useful optimizations, but can also cause critical miscompiles. (e.g. if guards later being compiled out of the program, causing security issues)

- (Note: Apparently there are compiler flags to force signed overflow to have defined behavior.

-fno-strict-overflow and -fwrapv)

How to handle overflow

- Ok, overflow is bad. What does one do about it?

- Even for the simplest operations of multiplication and addition, you need to be careful of how large the input operands can be, and whether overflow is possible.

- For application code, it might often be the case that numbers are so small that this is not a concern, but if you’re dealing with untrusted input, buffer sizes, or memory offsets, then you need to be more careful, as these numbers can be larger.

- In situations where you need to defend against overflow, you cannot just inline the whole arithmetic expression the natural way.

- You need to evaluate the expression operation by operation, at each step checking if overflow would occur, and failing the function if so.

- For example, here you’d first evaluate the multiplication in a checked fashion. And then if that succeeds, do the arithmetic.

- For addition

a + b, the typical check for size_t looks like: bool willOverflow = (a > SIZE_MAX - b);

- For multiplication

a * b, it looks like bool willOverflow = (b != 0 && a > SIZE_MAX / b);

- For signed ints, the checks are more involved. This is a reason to prefer unsigned types in situations where overflow checking is needed.

Helper libraries

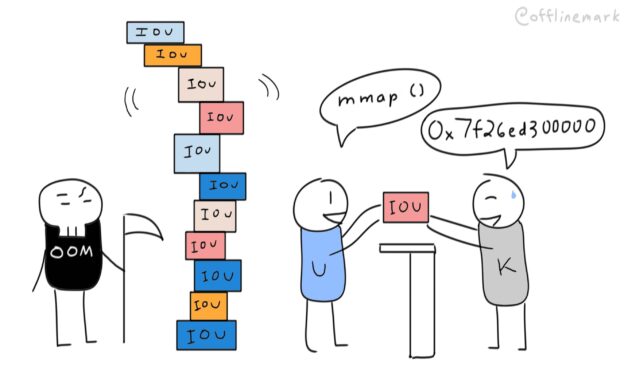

Manually adding inline overflow checking code everywhere is tedious, error prone, and harms readability. It would be nice if one could just write the arithmetic and spend less time worrying about the subtleties of overflow.

GCC and Clang offer builtins for doing checked arithmetic. They also have the benefit of checking signed integer overflow without UB.

In practice, it seems like some industrial C/C++ projects use helper utilities to make overflow-safe programming more ergonomic.

When to think about overflow

So when coding, when do you actually need to care about this?

You do not literally have to use checked-arithmetic for every single addition or multiplication in the program. Checked arithmetic clutters the code and can impact runtime performance, so you should only use it when it’s relevant.

It’s relevant when coding on the “boundary”. Arithmetic on untrusted or weakly trusted input data, e.g. from the network, filesystem, hardware, etc. Or where you’re implementing an API to be called by external users.

But for many normal, everyday math operations in your code, you probably don’t need it. (Unless you are particularly dealing with numbers so large that overflow is a possibility. So a certain amount of vigilance is needed.)

Rust

- Rust has significant differences from C/C++ for its overflow behavior, which make it much less error prone.

- Difference 1 – All overflow is defined, unlike signed overflow being UB in C/C++. This prevents critical miscompiles if signed overflow happens.

- What about logic bugs where numbers wrap around and produce dangerously large values that are mishandled down the line?

- Rust sometimes protects against these.

- Rust protects against these in debug builds by injecting overflow checks, which panic if this happens. This impacts performance, but debug builds are slow anyway, and this helps find bugs faster in development.

- In release builds, wrap-around logic bugs are still possible. Rust prevents undefined behavior and memory unsafety, but incorrect arithmetic can still cause panics, allocation failures, or incorrect program behavior.

- Difference 2 – Rust has first-class support for checked arithmetic operations in the form of “methods” one can call on an integer. These are a clean and ergonomic way to safely handle overflow if that is relevant for code.

Choosing an integer type

There are a lot of int types. Which do you choose?

- int

- unsigned int

- size_t

- ssize_t

- uint32_t, uint64_t

- off_t

- ptrdiff_t

- uintptr_t

Here’s my current understanding.

First, split off the specific-purpose types:

- off_t: (Signed) For file offsets

- ptrdiff_t: (Signed) for pointer differences

- uintptr_t: (Unsigned) For representing a pointer as an integer, in order to do math on it

Next, split off the explicit sized types: uint32_t, uint64_t, etc

These are mainly used when interfacing with external data: the network, filesystem, hardware, etc. (From C/C++! In Rust, it’s idiomatic to use explicit sized types in more situations).

That mostly leaves int vs size_t.

This is hotly debated. Here’s my rule of thumb:

- For application code, dealing with “small” integers, counts: Use

int. This lets you assert for non-negative. The downside is signed int overflow is UB, and thus dangerous, but the idea is that you should not be anywhere near overflowing since the integers are small. This is approximately the position of the Google Style C++ guide.

- For “systems” code dealing with buffer sizes, offsets, raw memory: Use size_t.

int is often too small for cases like this. size_t is “safer” in that overflow is defined. This is approximately the position of the Chromium C++ style guide.

In the above code that’s computing the buffer size, there’s a few reasons to avoid int.

First of all, int might be too small, depending on the usage case (e.g. generic libraries).

Secondly, it’s risky to use int because it’s easier to invoke dangerous UB. Since int overflow is UB, you risk triggering miscompiles (e.g. if guards being compiled out) if you accidentally overflow. This has caused many subtle security bugs.

In general, reasoning about overflow is more complicated with int than with size_t, since size_t has fully defined behavior.

However there are downsides of size_t. Notably, you can’t assert it as non-negative.

What about unsigned int?

Rule of thumb: Don’t use this. It’s a worse size_t because it’s smaller/undefined width, and a worse int because it can’t be asserted for non-negative.

What about ssize_t?

This is a size_t that can also contain negative values for error codes.

It seems somewhat useful, but is also error-prone to use, as it must always be checked for negativity before use as a size_t, otherwise you’ll have the classic issue where it produces a dangerously large unsigned variable.

In general, it seems like one should prefer explicit distinction between error state and integer state (e.g. bool return, and size_t out parameter, or std::optional<size_t>) over this.

Which types to choose for the example

The input arguments should be size_t, since we’re dealing with buffers, offsets, and raw memory.

The return value is a bit of a trick question. Any function like this must be able to return either a value, or an error if overflow happened.

The core return value should be size_t. But then how to express error in case of overflow?

std::optional<size_t> is a good choice if using C++.

ssize_t is an option, if using C.

But changing the signature to return a bool, and then having an out size_t parameter might be even better, and is the pattern used by the compiler builtins.

Related: